When you read a headline like "New Study Links Blood Pressure Drug to Deadly Heart Risks," it’s natural to panic. You might stop taking your medicine. You might call your doctor in a hurry. But what if the story got it wrong? What if the real risk was tiny, or the study didn’t even measure what the headline claimed? Medication safety reports in the media are everywhere-and most of them are misleading. You don’t need a medical degree to spot the red flags. You just need to know what to look for.

Don’t Trust Relative Risk Alone

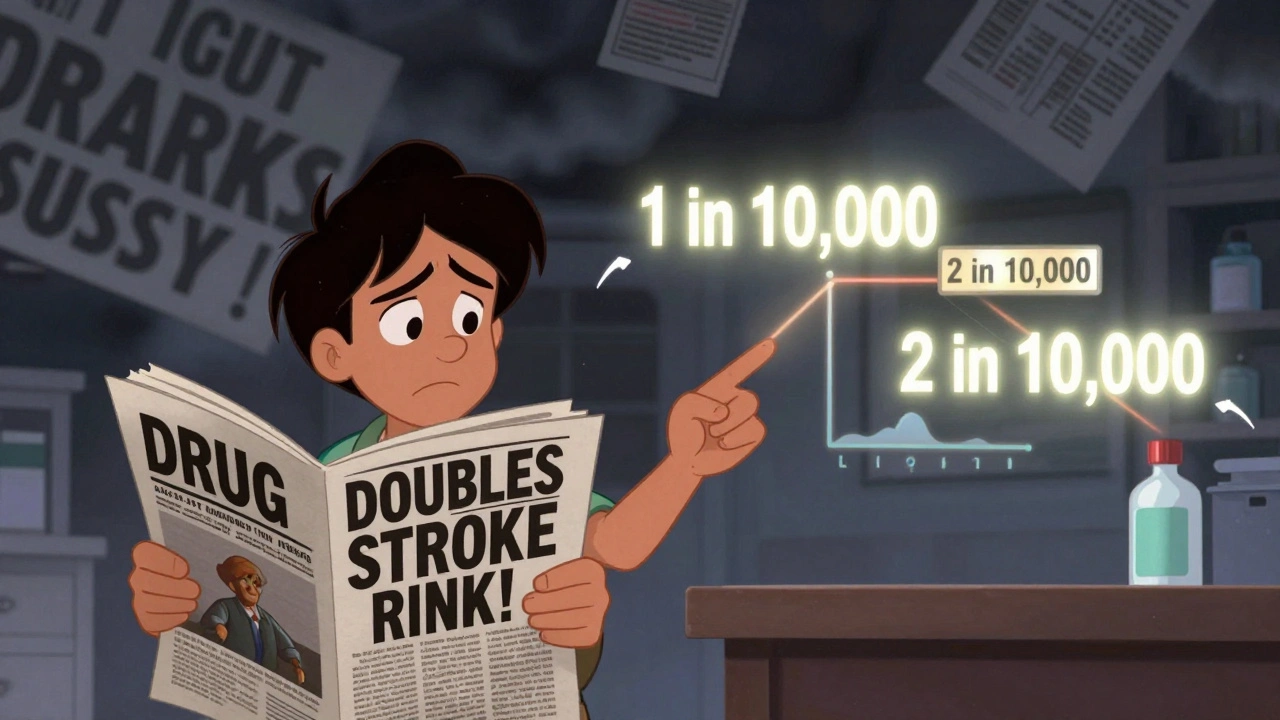

Media reports love to say things like, "This drug doubles your risk of stroke!" That sounds terrifying. But here’s the catch: doubling a tiny risk is still a tiny risk. If your chance of a stroke is 1 in 10,000, doubling it means 2 in 10,000. That’s still a 99.98% chance you won’t have one. Yet most stories leave out the starting number. A 2020 BMJ study found that only 38% of media reports included absolute risk-the actual chance of harm-when they mentioned relative risk. Without it, you’re being scared by math that doesn’t reflect reality.Understand the Difference Between Errors and Reactions

Medication errors and adverse drug reactions aren’t the same thing. An error is something that went wrong: a nurse gave the wrong dose, a pharmacist mixed up pills, a doctor prescribed something that interacts badly. An adverse drug reaction is a harmful effect from a drug taken correctly. One is preventable. The other isn’t always. A 2022 PLOS ONE review of 59 studies found that only 32% of research properly separated the two. And guess what? Most media reports don’t either. If a story says "Drug X caused 500 deaths," ask: Were these mistakes, or unavoidable side effects? The answer changes everything.Check the Study Method

Not all research is created equal. There are four main ways scientists study medication safety:- Incident report review: Hospitals report bad events. Easy, but misses most cases.

- Chart review: Researchers dig through medical records. Finds more problems, but still only catches 5-10% of actual errors.

- Direct observation: Someone watches doctors and nurses in real time. Most accurate, but expensive and rare.

- Trigger tool: Uses flags like sudden kidney failure or abnormal lab results to find potential problems. Best balance of accuracy and efficiency.

Look for Confounding Factors

Just because people on a drug had more heart attacks doesn’t mean the drug caused them. Maybe those patients were older, sicker, or had other conditions. Good studies control for these confounding factors. A 2021 audit in JAMA Internal Medicine found that only 35% of media reports described how researchers handled this. If the article doesn’t mention age, other medications, or pre-existing conditions, it’s likely oversimplifying. A real safety study adjusts for these things. A bad one just says, "People on this drug had more problems."Verify the Source

Many reports cite the FDA’s FAERS database or the WHO’s global safety system. But here’s the truth: these systems collect reports, not confirmed causes. Someone might report a heart attack after taking a drug-but the drug might have nothing to do with it. A 2021 study in Drug Safety found that 56% of media stories treated these reports as proof of harm. That’s wrong. FAERS is a starting point for investigation, not a death certificate for a drug. Always check: Did the study prove causation? Or just list a coincidence?

Compare With Official Guidelines

The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) and the Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) publish clear standards for safe medication use. ISMP even has a list of dangerous abbreviations-like “U” for units (which can be mistaken for “0”)-that still cause errors in hospitals. If a media report talks about medication safety but never mentions these organizations, it’s probably not grounded in real clinical practice. A 2022 analysis found that outlets using ISMP resources had 43% fewer factual errors. That’s not a coincidence.Watch for Sensationalism

Cable news and digital-only outlets are far worse than newspapers at explaining limitations. A 2020 BMJ study showed that only 18% of TV reports mentioned study flaws, compared to 47% in print. Social media? Even worse. A 2023 National Patient Safety Foundation report found that 68% of medication safety claims on Instagram and TikTok were inaccurate. Stories that say "This drug is killing people!" without context are designed to get clicks, not inform. The same study found that 61% of U.S. adults changed their medication use after reading a news story-and 28% stopped cold. That’s dangerous.Use Trusted Tools to Check Claims

You don’t have to guess. There are real tools you can use:- FAERS (FDA Adverse Event Reporting System): Search for reports, but remember-they’re not proof.

- ClinicalTrials.gov: Find the original study behind the headline.

- Leapfrog Hospital Safety Grades: See if the hospital mentioned in the story has been evaluated for medication safety.

- WHO ATC Classification: Check if the drug is correctly named and categorized.

Know the Bigger Picture

The global market for medication safety tools is growing fast-$3.2 billion in 2022, expected to hit $6.8 billion by 2030. That means companies, insurers, and even media outlets have financial stakes in how these stories are told. Direct-to-consumer drug ads have tripled since 2015. More ads mean more pressure to create fear-or reassurance-based on emotion, not evidence. And now, AI is generating health content. A 2023 Stanford study found that 65% of AI-written medication safety articles had major factual errors. So even if the headline looks professional, it might be wrong.

What to Do Next Time You Read a Story

Here’s a simple checklist:- Does it give the absolute risk-not just "doubled" or "tripled"?

- Does it distinguish between medication errors and adverse reactions?

- Does it name the study method (trigger tool, chart review, etc.)?

- Does it mention confounding factors like age, other drugs, or health conditions?

- Does it cite FAERS or WHO and clarify these are reports, not proven causes?

- Does it reference ASHP or ISMP guidelines?

- Does it mention study limitations?

When in Doubt, Talk to Your Pharmacist or Doctor

You don’t have to be an expert to ask smart questions. Bring the article. Say: "I read this. Can you help me understand if this applies to me?" Pharmacists see these stories every day. They know which ones are hype and which ones matter. A 2022 survey of 1.5 million doctors on Sermo gave media accuracy about medication safety a 5.2 out of 10. That’s barely passing. You’re better off trusting your healthcare team than a viral headline.Final Thought: Your Health Isn’t a Click

Medication safety matters. But fear doesn’t protect you-understanding does. The goal isn’t to avoid all drugs. It’s to use them wisely. That means asking questions, checking sources, and refusing to let a catchy headline make your decisions for you. The next time you see a scary story about a drug, pause. Ask: What’s missing? Then go find the truth.Can I trust media reports that say a drug is dangerous?

Not without checking the details. Most reports exaggerate risk by using relative risk instead of absolute risk, confuse medication errors with side effects, and fail to explain study limitations. Always look for the original study, check if it controlled for other health factors, and verify if the source is credible-like the FDA’s FAERS database or clinical trial records.

What’s the difference between a medication error and an adverse drug reaction?

A medication error is a preventable mistake-like giving the wrong dose, wrong drug, or wrong patient. An adverse drug reaction is a harmful side effect that happens even when the drug is taken correctly. Errors are about human or system failure. Reactions are about the drug’s biology. Media reports often mix them up, making it seem like a drug is unsafe when the real issue was a mistake in handling it.

Why do news stories say a drug "doubles the risk" when it’s still very low?

Because "doubles" sounds scary. It grabs attention. But if the original risk was 1 in 10,000, doubling it means 2 in 10,000-still extremely rare. Good reporting always includes both the relative risk (doubled) and the absolute risk (1 in 10,000). Most media don’t. That’s why you need to ask for the baseline number.

Are FDA reports proof that a drug causes harm?

No. The FDA’s FAERS system collects voluntary reports from patients and doctors. These are signals, not proof. For every reported event, many more go unreported. A report saying "100 people had heart attacks after taking Drug X" doesn’t mean Drug X caused them. It just means those events happened around the same time. Only controlled studies can prove causation.

What should I do if a news story makes me want to stop my medication?

Don’t stop. Call your doctor or pharmacist. Bring the article. Ask them to explain the study, the actual risk, and whether it applies to you. Stopping medication without guidance can be far more dangerous than the risk described in the story. Most media reports about drugs are incomplete or misleading. Your healthcare provider has the full picture.

Can AI-generated health articles be trusted?

Not reliably. A 2023 Stanford study found that 65% of medication safety articles written by AI tools contained serious factual errors-especially in how they described risk levels. AI doesn’t understand context or nuance. It mimics language but can’t judge quality. Always verify AI-generated health content with trusted sources like the FDA, WHO, or your healthcare provider.

How can I find the original study behind a news article?

Look for a link to a journal or clinical trial database like ClinicalTrials.gov or PubMed. If the article doesn’t provide one, search the drug name and study topic yourself. The original study will tell you the sample size, methods, limitations, and whether the results were statistically significant. Most media reports skip these details-but the original study won’t.

Next Steps: How to Protect Yourself

- Keep a list of your medications and why you take them. - Talk to your pharmacist every time you get a new prescription-they spot interactions you might miss. - Bookmark FAERS and ClinicalTrials.gov. Use them when you see a scary headline. - Avoid social media for health decisions. Instagram and TikTok have the highest rates of medication misinformation. - If you’re unsure, wait 48 hours. Don’t make urgent decisions based on fear. - Share accurate information. If you see a misleading post, comment with a link to a credible source.Medication safety isn’t about avoiding all risk. It’s about making informed choices. The media isn’t your doctor. Your doctor isn’t your algorithm. And your health? That’s yours to protect-with facts, not fear.

Arjun Deva

December 6, 2025 AT 17:57So... the FDA is just lying to us? And the WHO? And every single drug company? It’s all a conspiracy to make us take poison!!! I’ve been reading this stuff for years-my cousin’s neighbor’s dog died after taking aspirin!!! They’re hiding the truth!!!

Inna Borovik

December 7, 2025 AT 03:00Let’s be clear-this guide is technically accurate but dangerously naive. You assume people care about absolute risk. They don’t. They care about fear. The media exploits that. And you’re giving them a checklist? That’s like handing a drunk person a map to the nearest bar. The system is broken. Not the headlines-the entire feedback loop.

Jackie Petersen

December 9, 2025 AT 00:08USA is the only country that lets drug companies advertise directly to people. That’s why this is such a mess. In Germany, they don’t scream ‘DOUBLING RISK!’ they just say ‘possible side effect: nausea.’ No drama. No clicks. No panic. We’re the circus. And we love it.

Annie Gardiner

December 10, 2025 AT 15:02What if the real danger isn’t the drugs… but the belief that we can ever truly understand them? Science is just a story we tell ourselves to feel safe. Maybe the ‘absolute risk’ is just another illusion. Maybe we’re all just atoms swirling in a universe that doesn’t care if we live or die. But hey-here’s a chart. Let’s make it pretty.

Rashmi Gupta

December 12, 2025 AT 06:07People in India don’t even have access to most of these drugs. Why are we wasting time on this? We’re still fighting for basic antibiotics. This feels like a rich person’s problem. Meanwhile, my aunt is taking diabetes pills she got from a street vendor. Who’s really at risk here?

Andrew Frazier

December 12, 2025 AT 06:50LOL this is why america is weak. You read a headline and you cry? You don’t trust your doctor? You need a checklist? My grandpa took 12 pills a day and lived to 98. He didn’t read no journal. He trusted his gut. You people are too soft. Stop overthinking. Just take the damn pill.

Kumar Shubhranshu

December 13, 2025 AT 23:01Chart reviews catch 5-10% of errors. That’s it. So 90% of harm is invisible. That’s terrifying. And you think a checklist fixes that? No. The system is designed to hide this. The real answer? Don’t take anything unless you absolutely have to.

Mayur Panchamia

December 15, 2025 AT 05:30AI-generated articles? HA! You think that’s bad? Try reading the FDA’s own website-half the links are broken, the fonts are 1998-era, and the language reads like it was translated by a drunk bureaucrat from Mars. Meanwhile, TikTok has better graphics and 10x more truth. The system is a dumpster fire. And you’re handing out pamphlets?

Saketh Sai Rachapudi

December 16, 2025 AT 04:10you know what the real problem is? PEOPLE ARE LAZY. they dont want to think. they want a headline. they want to panic. then they want someone else to fix it. thats why we have this mess. its not the media. its US. we are the problem. stop blaming the news. look in the mirror.

Akash Takyar

December 17, 2025 AT 15:43Thank you for this thoughtful, well-researched guide. It’s rare to see such clarity in a world of noise. I’ve shared this with my entire family, especially my elderly parents who are on five different medications. A simple checklist like this could save lives. Please keep writing. The world needs more of this.

Kenny Pakade

December 18, 2025 AT 23:50Oh so now we’re supposed to trust doctors? After everything they’ve done? They’re in bed with Big Pharma. They get kickbacks. They push pills to hit quotas. You think your pharmacist is your friend? She’s got a quota to meet. You’re being played. Again.

brenda olvera

December 19, 2025 AT 19:55I love this. So many of us are scared to ask questions. But you’re right-your pharmacist knows more than your doctor sometimes. I brought my article to mine last week and she laughed and said ‘this is trash, honey.’ Then she showed me the real data. Best 10 minutes of my life.

Myles White

December 21, 2025 AT 03:55It’s interesting how this entire conversation hinges on the assumption that people want truth. But what if what people really want is narrative? A clear villain, a clear hero, a clear ending? That’s what sells. That’s why headlines say ‘drug doubles risk’-because it’s a story. The truth? It’s messy. It’s probabilistic. It’s boring. And we’re not wired for boring. We’re wired for drama. So maybe the real problem isn’t the media-it’s human nature.

olive ashley

December 22, 2025 AT 03:59AI writes 65% of health articles with errors? No surprise. I once read an article that said ‘aspirin causes brain cancer’ and it was written by a bot that confused ‘aspirin’ with ‘aspartame.’ And people believed it. That’s not misinformation. That’s cognitive collapse. We’re not just misinformed-we’re mentally unmoored.

Ibrahim Yakubu

December 23, 2025 AT 20:43Let me tell you something. In Nigeria, we don’t have time for checklists. We have three pills. One is fake. One is expired. One might work. We take them all. We pray. We hope. We survive. Your ‘absolute risk’? We don’t have that luxury. We have survival risk. And that’s the only number that matters.