What Is Polycystic Kidney Disease?

Polycystic kidney disease, or PKD, is a genetic condition where fluid-filled sacs-called cysts-grow inside the kidneys. Over time, these cysts multiply and expand, slowly replacing healthy kidney tissue. As the kidneys fill with cysts, they lose their ability to filter waste and regulate fluids. Eventually, this leads to kidney failure. In the U.S., about 600,000 people live with PKD, making it the most common inherited kidney disorder and the fourth leading cause of kidney failure.

There are two main types: autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) and autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease (ARPKD). ADPKD is by far the most common, making up more than 98% of all cases. ARPKD is rare and usually shows up in infancy or early childhood. Both types are caused by mutations in specific genes that control how kidney cells grow and form structures. Without these genes working right, cells don’t stop growing-they keep forming cysts instead of normal kidney tissue.

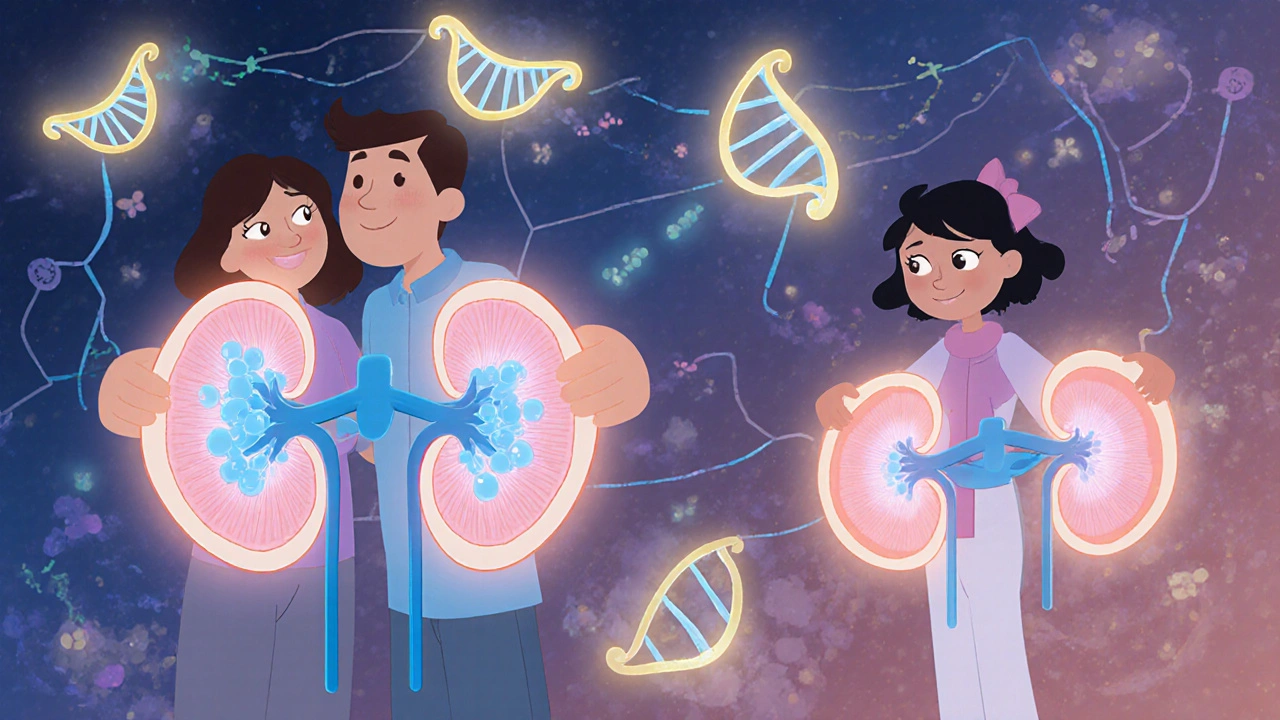

The Genetics Behind PKD: How It’s Passed Down

PKD doesn’t come out of nowhere. It’s inherited. If you have ADPKD, you got it from a parent-or, in about 10% of cases, from a brand-new mutation in your own DNA. The gene mutation is dominant, meaning you only need one bad copy to get the disease. Two genes are responsible: PKD1 and PKD2. About 78% of ADPKD cases are linked to PKD1, which tends to cause more severe disease. PKD2 accounts for 15% and usually progresses slower.

ARPKD is different. It’s recessive. That means you need two bad copies-one from each parent. Parents who carry just one copy usually don’t have symptoms. But if both parents are carriers, each child has a 25% chance of having ARPKD. This type often shows up right after birth, with enlarged kidneys and breathing problems. Some babies don’t survive the first few weeks. Others live into childhood, but many develop high blood pressure and liver scarring.

Even within families, the disease can vary wildly. Two siblings with the same PKD1 mutation might have very different outcomes. One might need a transplant at 45; another might keep good kidney function into their 70s. Scientists believe other genes and environmental factors play a role in how fast cysts grow-but we don’t yet know all the pieces.

When Do Symptoms Show Up?

For most people with ADPKD, symptoms don’t appear until their 30s or 40s. That’s why many don’t realize they have it until they start feeling pain, notice blood in their urine, or get diagnosed during a routine check-up for high blood pressure. But it’s not always that simple. Some children with ADPKD develop high blood pressure as early as age 5. In rare cases, kidney function drops so fast that teens need dialysis.

ARPKD is different. Symptoms often appear at birth. Babies might have swollen bellies due to enlarged kidneys, trouble breathing, or poor growth. Liver problems are common too-cysts can form in bile ducts, leading to scarring and portal hypertension. That’s why ARPKD is often called a liver-kidney disorder.

One of the biggest red flags is family history. If a parent has PKD, you have a 50% chance of inheriting ADPKD. Yet, many people go years without being tested. One Reddit user shared that it took seven years and three doctors before they got a correct diagnosis-even though their father had PKD. That delay is common. Doctors don’t always think to test for it unless symptoms are obvious.

How Is PKD Diagnosed?

Doctors use a mix of imaging and genetics to confirm PKD. The most common test is an ultrasound. For someone with a family history of ADPKD, finding at least 10 cysts in each kidney by age 30 is a strong sign of the disease. If you’re younger, fewer cysts might still be enough. CT scans and MRIs give more detail, especially if cysts are hard to see on ultrasound.

Genetic testing is becoming more common. It’s not always needed, but it helps when the diagnosis isn’t clear. Maybe the person has no family history, or the cysts are fewer than expected. Testing looks for mutations in PKD1, PKD2, and PKHD1. The cost is around $1,200, and it’s covered by many insurance plans if there’s a strong clinical reason. It’s especially useful for people thinking about having kids, since it can tell them their risk of passing PKD on.

Doctors also check kidney function with blood and urine tests. The estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) tells you how well the kidneys are filtering. A normal eGFR is above 90. Once it drops below 60, it signals moderate kidney damage. In PKD, eGFR usually declines by 4-6 mL/min per year, but that varies a lot from person to person.

How Is PKD Managed Today?

There’s no cure for PKD-but there are ways to slow it down and manage symptoms. The most important thing is controlling blood pressure. High blood pressure speeds up kidney damage. The goal is to keep it below 130/80 mmHg. Most patients start with ACE inhibitors or ARBs, which not only lower blood pressure but also reduce protein in the urine-a sign of kidney stress.

The only FDA-approved drug specifically for ADPKD is tolvaptan (brand name Jynarque). It works by blocking a hormone called vasopressin, which tells kidney cells to make more fluid. Less vasopressin means slower cyst growth. Clinical trials showed it reduces kidney enlargement and slows eGFR decline by about 1.3 mL/min per year. But it’s expensive-around $115,000 a year-and has side effects like extreme thirst and frequent urination. It’s only recommended for people with rapidly progressing disease, usually confirmed by imaging showing fast-growing kidneys.

Other strategies include drinking plenty of water, avoiding caffeine, and limiting salt. Some studies suggest that staying well-hydrated might help slow cyst growth. Avoiding NSAIDs like ibuprofen is also key-they can hurt the kidneys further. Regular exercise and a healthy diet help manage weight and blood pressure, both of which protect kidney function.

What Happens When Kidneys Fail?

By age 70, about 75% of people with ADPKD will need dialysis or a kidney transplant. That’s a big number-but it’s not the end. Dialysis can keep people alive for years. A transplant gives the best quality of life. Most PKD patients do very well after transplant, since the disease doesn’t come back in the new kidney.

The wait for a kidney can be long-3 to 5 years on average. Blood type and location matter. People with rare blood types wait longer. Some choose to join the living donor program, where a healthy relative or friend donates a kidney. That’s often faster and leads to better outcomes.

Even after transplant, patients need lifelong care. Immunosuppressants prevent rejection, and regular check-ups catch problems early. Many transplant recipients return to work, travel, and even have children.

What’s on the Horizon?

Research is moving fast. Tolvaptan was the first drug to target the root cause of ADPKD-but it’s not perfect. New drugs are in late-stage trials. Lixivaptan, another vasopressin blocker, showed similar results in early studies and may be cheaper. Bardoxolone methyl, originally developed for diabetic kidney disease, improved eGFR in PKD patients by nearly 5 mL/min over 48 weeks in a phase 2 trial.

There’s also hope in gene therapy and CRISPR-based treatments. Scientists are testing ways to turn off the faulty PKD1 gene in animal models. It’s still years away from humans, but it’s no longer science fiction.

Meanwhile, better imaging and AI tools are helping predict who’s at risk for rapid decline. If we can spot fast progressors early, we can start treatment sooner and save more kidney function.

Living With PKD: Real Challenges and Real Hope

Chronic pain is the most common complaint. About 78% of patients report moderate to severe pain from enlarged kidneys, cysts bursting, or kidney stones. Many need pain medication, but opioids are risky for kidney patients. Physical therapy, heat packs, and nerve blocks help some.

Anxiety is another big issue. Knowing your kidneys will likely fail by middle age is heavy. But many find strength in community. Online groups like the PKD Foundation and Reddit’s r/kidneydisease offer support, advice, and shared experiences. One patient wrote: “Starting blood pressure control at 28 kept my eGFR stable at 65% at age 45.” That’s the kind of story that gives hope.

PKD isn’t just a kidney disease. It affects your life-your work, your relationships, your future. But with early diagnosis, good care, and new treatments on the way, people are living longer, healthier lives than ever before.

Is polycystic kidney disease hereditary?

Yes, PKD is almost always inherited. ADPKD, the most common type, follows an autosomal dominant pattern: if one parent has it, each child has a 50% chance of inheriting the mutated gene. About 10% of cases come from new mutations with no family history. ARPKD is recessive, meaning both parents must carry a mutated gene for a child to be affected.

Can PKD be cured?

There is no cure yet. But treatments like tolvaptan can slow the progression of ADPKD. Managing blood pressure, staying hydrated, and avoiding kidney stressors can help preserve function longer. For those who reach kidney failure, dialysis and transplant are life-saving options.

How do I know if I have PKD?

If you have a family history of PKD and start experiencing high blood pressure, flank pain, blood in urine, or frequent urinary tract infections, talk to your doctor. Diagnosis usually starts with an ultrasound to look for kidney cysts. Genetic testing can confirm the mutation if the diagnosis is unclear or if you’re planning a family.

What’s the difference between PKD1 and PKD2?

PKD1 mutations cause more aggressive disease. People with PKD1 typically reach kidney failure about 20 years earlier than those with PKD2-on average in their late 50s versus late 70s. PKD1 is also linked to more severe cyst growth and higher rates of complications like liver cysts and brain aneurysms.

Can someone with PKD have children?

Yes, many people with PKD have healthy children. But if you have ADPKD, each child has a 50% chance of inheriting the disease. Genetic counseling and prenatal testing are available to help families understand their risks. For ARPKD, both parents must be carriers for a child to be affected, so testing both partners is important if there’s a family history.

Chrisna Bronkhorst

November 11, 2025 AT 01:02And don’t get me started on tolvaptan. $115k/year? That’s not medicine, that’s a ransom note. Pharma’s laughing all the way to the bank while families sell homes to afford it.

Amie Wilde

November 11, 2025 AT 05:18Gary Hattis

November 11, 2025 AT 09:27That’s the real problem. Cultural silence kills. We need more open conversations, especially in immigrant families. Genetic testing should be part of routine family health history - not a luxury.

Esperanza Decor

November 13, 2025 AT 04:18People think this is just ‘kidney stuff.’ It’s not. It’s your entire future. But you can still live well. I’m training for a half-marathon. I’m not waiting to die. I’m fighting.

Deepa Lakshminarasimhan

November 14, 2025 AT 12:19Erica Cruz

November 16, 2025 AT 04:36Meanwhile, the real solution - hydration, low-salt diet, avoiding NSAIDs - is free. But you can’t patent water. So they sell you a $115k pill instead.

Johnson Abraham

November 17, 2025 AT 12:23my bro got it. he drinks like 10 gatorades a day now. says it helps. idk. i think he’s just addicted to sugar now. also he hates ibuprofen. says it’s ‘bad for the cysts.’ whatever man. i just hope he don’t need a transplant. that shit sounds scary.

Shante Ajadeen

November 18, 2025 AT 00:17And please, talk to your family. My patient last week found out her 16-year-old daughter had it because she finally asked her dad to get tested. That’s the power of asking. You can still live a full life. I’ve seen people with PKD raise kids, travel, start businesses. It’s not the end. It’s just a new chapter.

dace yates

November 18, 2025 AT 21:26Danae Miley

November 19, 2025 AT 22:51Charles Lewis

November 20, 2025 AT 17:07Furthermore, the emerging data on tolvaptan, while compelling, must be contextualized: its benefit is most pronounced in patients with rapidly enlarging kidneys, as measured by total kidney volume on serial MRI, and in those under 50 with preserved eGFR.

Patients often overlook the importance of avoiding nephrotoxins - NSAIDs, contrast dye, excessive protein intake - and these are equally vital.

Finally, the psychological burden is profound. We must integrate mental health support into routine PKD care. This is not just a renal disease - it is a life-altering condition that demands holistic, multidisciplinary management.