Warfarin Dosing Calculator

Calculate Your Warfarin Starting Dose

This calculator estimates your recommended warfarin starting dose based on genetic factors that affect your body's response to the medication. Your genes can significantly impact how you metabolize warfarin and how sensitive you are to its effects.

Recommended Starting Dose

Genetic Profile Explanation: Your CYP2C9 variant affects how quickly your body breaks down warfarin. Your VKORC1 variant affects how sensitive you are to warfarin's effects. Together, these determine your optimal starting dose.

Every year, millions of people start taking warfarin to prevent dangerous blood clots. But for a lot of them, getting the dose right is a nightmare. One week they’re fine, the next they’re in the ER with an INR of 7.2. Why does this happen? It’s not always about diet, alcohol, or other meds. Sometimes, it’s written in your genes.

Why Warfarin Is So Hard to Dose

Warfarin isn’t like other blood thinners. It doesn’t have a predictable effect. Two people taking the same 5 mg daily dose can have wildly different responses. One stays safely in range, the other bleeds internally. This isn’t random. It’s biology.

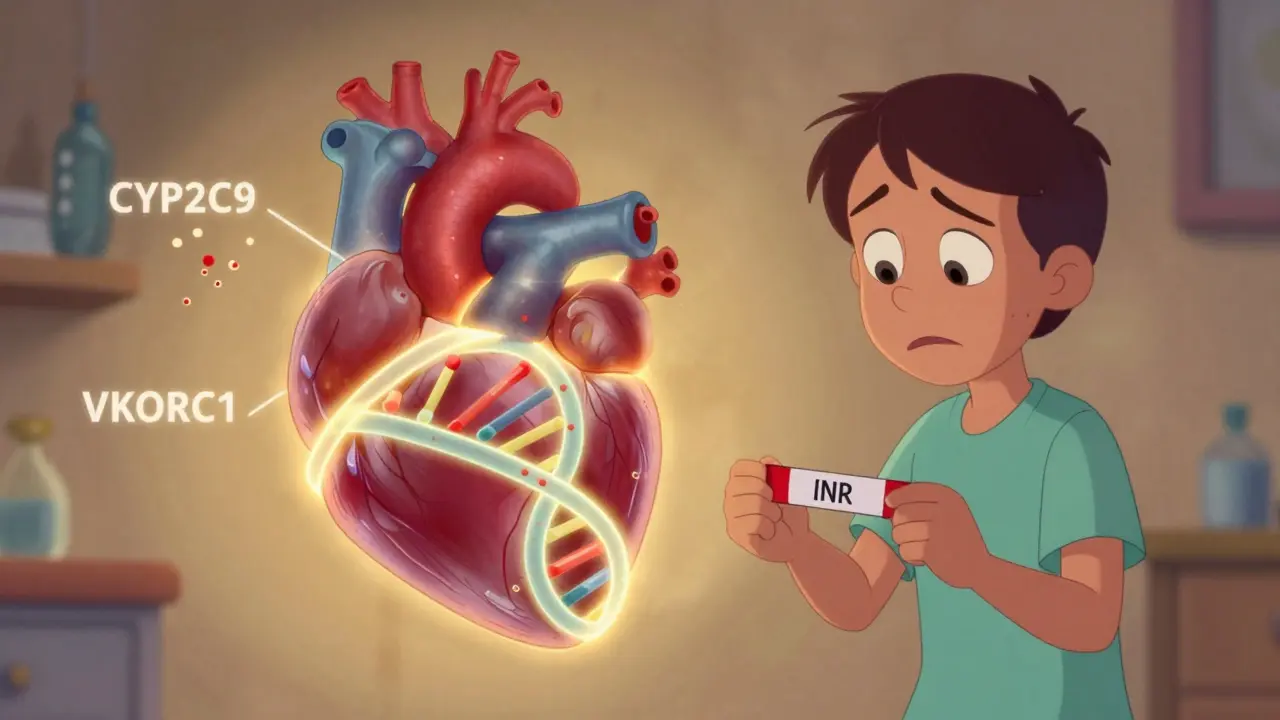

Warfarin works by blocking VKORC1, the enzyme your liver needs to recycle vitamin K. Without that, clotting factors can’t form properly. But here’s the catch: your body breaks down warfarin using another enzyme called CYP2C9. If either of these two systems is genetically slower, the drug builds up. Too much warfarin means too thin blood. That’s when INR spikes and bleeding happens.

The problem? Most doctors start everyone at 5 mg. That’s the standard. But for someone with a slow CYP2C9 variant, that’s like pouring gasoline on a fire.

The Two Genes That Control Your Warfarin Response

Two genes dominate how you react to warfarin: CYP2C9 and VKORC1.

CYP2C9 is the metabolizer. It chops up the active part of warfarin (the S-enantiomer) so your body can flush it out. But some people have variants-CYP2C9*2 and CYP2C9*3-that make this enzyme work poorly. People with CYP2C9*3 clear warfarin up to 80% slower than normal. That means even a tiny dose can pile up. One study showed carriers of this variant had an 83% higher chance of hitting an INR over 4 in the first week.

VKORC1 is the target. The gene tells your body how much of the warfarin-blocking enzyme to make. The -1639G>A variant (rs9923231) is the big one. If you have two A alleles (AA), your body makes about 40% less of this enzyme. That means warfarin hits harder. You don’t need much to get the job done. People with AA genotypes often need just 5-7 mg per week. Someone with GG might need 28-42 mg. That’s a six-fold difference.

Combine both bad variants? You’re in high-risk territory. A 2020 review found these patients had nearly double the risk of dangerous over-anticoagulation in the first week. And it’s not rare. About 1 in 5 white people carry at least one slow CYP2C9 variant. Nearly 1 in 3 have the low-dose VKORC1 genotype.

Real People, Real Consequences

Numbers don’t tell the whole story. Real patients live with the fallout.

One Reddit user, u/WarfarinWarrior, spent six months bouncing between INR 2.1 and 6.5. His doctor kept adjusting his dose up and down, blaming his diet. Then he got tested. He had the CYP2C9*3 variant. His dose dropped from 5 mg to 2.5 mg-and his INR stabilized within weeks.

Another user, u/ClottingConfused, started at the standard 5 mg after a pulmonary embolism. His doctor didn’t test his genes. Two weeks later, he ended up in the ER with an INR of 6.2. He bled into his thigh. He needed a transfusion.

These aren’t outliers. A 2018 study found that 68% of people with CYP2C9 variants had at least one INR above 4 in the first three months. Only 42% of those without the variants did. And the bleeding rate? 18.7% vs. 9.3%.

Does Genetic Testing Actually Help?

Yes. But not always the way you think.

The EU-PACT trial in 2013 showed genotype-guided dosing reduced major bleeding by 32% in the first 90 days. The 2025 European Heart Journal meta-analysis confirmed that: a 27% drop in major bleeds. Time spent in the therapeutic range improved by nearly 8%. That’s not a small win. That’s life-saving.

But here’s the catch: it only helps if you test before you start. Testing after you’ve already bled is too late. And it only matters if the doctor actually uses the results.

At Vanderbilt University, when they integrated genetic results into their electronic records, patients reached a stable INR 1.8 days faster. That’s less time in the danger zone.

Yet, only 5-15% of U.S. patients get tested before starting warfarin. Why? Because many doctors don’t know how to interpret the results. A 2023 survey found only 38% of primary care doctors could correctly explain how CYP2C9*3 affects metabolism. And insurance? Often denies coverage. One survey found 61.5% of patients were frustrated by the cost-$250 to $500 out of pocket.

Who Should Get Tested?

You don’t need testing if you’re on warfarin for just a few weeks after surgery. But if you’re on it long-term-for atrial fibrillation, deep vein thrombosis, or a mechanical heart valve-you should.

Here’s who benefits most:

- People starting warfarin for chronic conditions

- Those with a history of bleeding on warfarin

- Patients with unexplained INR swings

- Anyone of European or Asian descent (these variants are more common)

- People taking other drugs that interact with CYP2C9, like amiodarone or fluconazole

The Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) gives clear guidelines: if you’re on warfarin long-term, test for CYP2C9 and VKORC1 before the first dose. They’ve even built dosing tables based on genotype combinations.

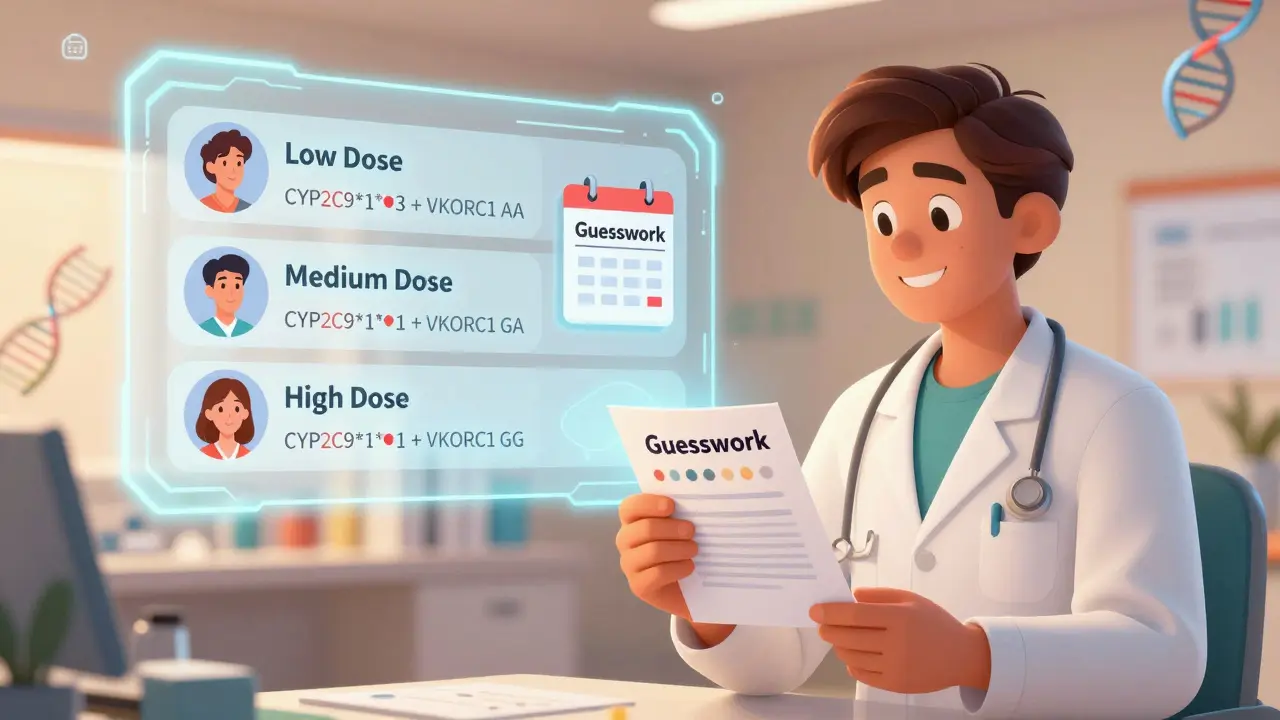

Low dose group: CYP2C9*1/*3 + VKORC1 AA → 0.5-2 mg/day

Medium dose: CYP2C9*1/*1 + VKORC1 GA → 3-4 mg/day

High dose: CYP2C9*1/*1 + VKORC1 GG → 5-7 mg/day

These aren’t guesses. They’re backed by data from over 10,000 patients.

Why Are DOACs Taking Over?

Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs)-like apixaban, rivaroxaban, dabigatran-don’t need genetic testing. They don’t need weekly blood tests. They’re easier. And that’s why their use jumped from 32% to 58% of new atrial fibrillation patients between 2010 and 2018.

But warfarin isn’t dead. It’s still the only option for mechanical heart valves. It’s cheaper. And if you bleed, you can reverse it with vitamin K or fresh plasma. DOACs don’t have that luxury.

So the real question isn’t “warfarin or DOAC?” It’s “which one fits your life?”

If you’re young, active, and don’t want to deal with blood tests, DOACs win. But if you’re on warfarin long-term and keep having bad INR readings, genetics might be the missing piece.

What’s Changing Now?

The tide is turning. In 2024, the FDA approved the GeneSight Psychotropic test to include warfarin genetics. The University of Florida launched the Warfarin Genotype Implementation Network (WaGIN) in early 2025, aiming to enroll 50,000 patients across 200 sites. They’re tracking outcomes in real time.

Costs are falling. Tests that cost $500 in 2025 are projected to drop below $100 by 2027. Medicare already covers CYP2C9 and VKORC1 testing under CPT codes 81225 and 81227. More insurers will follow as evidence piles up.

By 2030, experts predict 60% of new warfarin starts will include genetic testing. That’s not hype. It’s science catching up to practice.

What You Can Do Right Now

If you’re on warfarin and your INR keeps swinging:

- Ask your doctor if you’ve ever been tested for CYP2C9 or VKORC1.

- If not, ask for a referral to a pharmacist or hematologist who understands pharmacogenetics.

- Check if your insurance covers it. If not, ask about cash pricing-some labs offer tests for under $200.

- If you’re starting warfarin soon, request testing before your first dose.

This isn’t about fancy science. It’s about avoiding the ER. It’s about not spending months guessing your dose. It’s about knowing your body, not fighting it.

Warfarin doesn’t have to be a gamble. Your genes already gave you the answer. You just need to ask for it.

Can I get tested for CYP2C9 and VKORC1 without a doctor’s order?

No. Genetic testing for warfarin requires a prescription. You can’t order it online like a home DNA kit. The test must be ordered by a licensed provider because the results directly affect your medication dose. Labs like LabCorp and Quest offer the tests, but only with a doctor’s requisition. Some telehealth services now offer pharmacogenetic consultations and can order the test for you.

How long does it take to get warfarin genetic test results?

Most labs deliver results in 3 to 5 business days. Some urgent services can turn it around in 48 hours. The turnaround time is usually fast enough to guide your first dose if you get tested before starting warfarin. If you’re already on it, results can still help adjust your dose within a week or two.

If I have a slow CYP2C9 variant, does that mean I’ll always need a lower dose?

Yes. Once you have a CYP2C9*2 or *3 variant, your body will always metabolize warfarin more slowly. That means you’ll need a lower dose than average for the rest of your life, even if you change medications or health conditions. The gene doesn’t change. Your dose might adjust slightly over time due to age, weight, or other drugs, but you’ll never need the same dose as someone without the variant.

Do I need to get tested again if I switch from warfarin to a DOAC?

No. Genetic testing for CYP2C9 and VKORC1 only matters for warfarin. DOACs like apixaban or rivaroxaban are metabolized differently and aren’t affected by these genes. Once you switch, the test results become irrelevant for your current treatment. But keep them on file-some future medications might still be impacted by your CYP2C9 status.

Is genetic testing for warfarin covered by Medicare?

Yes. Medicare covers CYP2C9 (CPT code 81225) and VKORC1 (CPT code 81227) testing when ordered for patients starting or adjusting warfarin therapy. Coverage requires medical necessity, meaning you’re either starting long-term anticoagulation or have had unstable INR readings. Most private insurers follow Medicare’s lead, but prior authorization is often required. Always check with your provider before testing.

Oladeji Omobolaji

January 22, 2026 AT 23:58Man, I never thought my genes could be the reason my INR kept jumping. I’m from Nigeria, and we don’t even talk about this stuff here. But after reading this, I’m gonna ask my doc if they test for this. No more guessing games.

Janet King

January 24, 2026 AT 14:36Genetic testing prior to warfarin initiation is clinically indicated for patients with long-term anticoagulation needs. The evidence base supporting genotype-guided dosing is robust and reproducible across multiple large-scale trials. Failure to implement this standard of care increases preventable adverse events.

dana torgersen

January 25, 2026 AT 21:19Okay, so… CYP2C9*3… and VKORC1… AA… and like… wow… I just… I mean, it’s not just ‘oh, maybe I’m sensitive’… it’s literally… my DNA is screaming at me to take less… and no one told me?… I feel… violated?… by the medical system… I’m not even mad… just… stunned…

Kerry Moore

January 27, 2026 AT 03:59This is one of the clearest summaries of pharmacogenetic implications in anticoagulation therapy I’ve encountered. The integration of real patient narratives alongside clinical data elevates the piece from informative to impactful. The data on bleeding rates and time to therapeutic INR strongly support routine pre-treatment genotyping for high-risk populations.

Laura Rice

January 27, 2026 AT 23:27I had a cousin who bled out from a nosebleed on warfarin… they thought it was ‘bad luck’… turns out she had the *3 variant… and her doctor just kept increasing her dose because ‘she wasn’t responding’… I cried reading this. We need to change this. Please. Someone. Tell your doctor. Get tested. It’s not hype-it’s survival.

Susannah Green

January 29, 2026 AT 02:17My mom’s been on warfarin for 12 years. Her INR used to swing like a pendulum-sometimes 2.1, sometimes 8.0. She got tested last year. Turns out: CYP2C9*1/*3 + VKORC1 GA. Dose dropped from 7.5mg to 3.5mg. She hasn’t been to the ER since. This isn’t science fiction. It’s common sense.

Sue Stone

January 30, 2026 AT 23:11My cousin got her test results back and her doctor just shrugged and said, ‘We’ve always done it this way.’ So she switched to apixaban. No more blood tests. No more panic. And she’s fine. Sometimes the best solution is just… switching drugs.

Vanessa Barber

January 31, 2026 AT 02:57So let me get this straight-you’re saying we should test everyone’s genes before giving them a pill? Next you’ll want us to sequence their ancestors before they eat cereal.

Sallie Jane Barnes

February 1, 2026 AT 08:01To everyone who says this is too expensive or too complicated: I’ve seen families shattered by preventable bleeds. This isn’t a luxury-it’s a lifeline. If you’re on warfarin long-term, ask for the test. If your doctor says no, find one who will. Your life is worth more than a $200 test.